It would be difficult to overstate the significance of Jamie Kalven’s role in Chicago’s journalism world. A founder of the Invisible Institute and now a regular fixture at the Intercept, Kalven has been amplifying Chicago’s unheard voices for decades. But he’s been most recently celebrated for his invaluable role in bringing the LaQuan McDonald killing into the public consciousness. He and his associates were directly responsible for unearthing or discovering three of the major elements that helped convict Officer Jason Van Dyke: an unimpeachable eyewitness to the shooting, the McDonald autopsy and, ultimately, pointing the way to the damning dash-cam video.

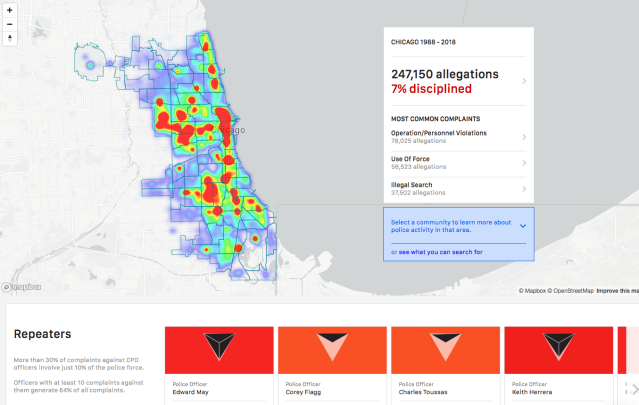

A few weeks ago, the Institute released a powerful update to its public data-base that tracks decades of reports about police misconduct in Chicago. It’s called the Citizens’ Police Data Project, and it contains almost a quarter-million citizen reports. Unique among similar data projects in other cities, Kalven says, is the fact that this data-base includes the names of the accused officers. Toward the end of the hour, Kalven takes us on a brief tour of the site’s features.

Much of our conversation today centers around the aftermath of the Jason Van Dyke trial, a trial that might not have happened at all, it can be argued, without the work of Kalven and his associates.

The engagement began when a still-unrevealed source “within law enforcement who reached out with the information that that shooting last week was not at all what was reported,” he tells us. “It was horrific. He disclosed that there was video and gave information that enabled me ultimately to find a civilian witness, a couple of civilian witnesses.”

Serious gravity was added to the case when Kalven was able to obtain a copy of the McDonald autopsy, which for the first time revealed evidence that contradicted that police narrative. Ultimately, Kalven obtained it through FOIA, and immediately released it to the public. But he enlisted a powerful ally.

“I reached out to Toni Preckwinkle, the President of the Cook County Board who is over the medical examiner and I described what I knew about the case to her and I asked if she would inquire of the medical examiner the substance of the autopsy.”

A kind of very-high-level FOIA request, we suggest.

“Yeah, ” he agrees, “and a good friend to have in these circumstances, but the prevailing story of what happened is aggressive young man with a knife lunges at a police officer. The police officer shoots in self-defense, defense of his fellow officers.”

And at this point, it should be remembered, nobody had heard the term “sixteen shots.”

“The sense was he was shot in the chest, died sometime later in a nearby hospital. That was the story…And so Toni Preckwinkle made an inquiry of the medical examiner and we live close to each other on the south side and I was actually going out for a run in the evening, a cold December night, snow falling and she drove up alongside me and beckoned me into her car…As I recall it she didn’t even say hello. She immediately said, “16 shots front and back,” and that was the first time I heard those words and it continued to reverberate. And then not too long after that I was able to FOIA the autopsy. Armed with this information, Kalven wrote the article “Sixteen Shots” in Slate in February 2015, which ignited the firestorm. “She told me 16 shots and at that point I could begin to write the article that ultimately appeared,” he says.

The article, incidentally, is well worth re-reading in this post-trial environment.

===

After Kalven released his finding that there’s a video, a media frenzy developed as demands for the video’s release erupted. Working with a young journalist named Brandon Smith and community activist Will Calloway, Kalven’s lawyers brought suit and ultimately won a ruling that the video must be released.

Kalven was skeptical that anything would happen soon. He saw it as part of a glacial process, including appeals and other legal wrangling, that could drag the release out for another year or more. But something unexpected happened. “And for reasons that are still somewhat complicated and mysterious things played out the way they did and it was released,” he tells us.

It’s a complicated combination of issues, largely about interagency responsibilities. The States’ Attorney and the US Attorney were running the investigation, he explains, and the Police Department and IPRA (the agencies they’d FOIA’d), “weren’t engaged in active investigation. They had sort of stepped down, and so there was no showing of harm from the release of the video. So what was going on between those different agencies is sort of fascinating.”

“I have had conversation with people high in the mayor’s office about why they released it,” Kalven continues, “and I think they were also surprised – it was the mayor’s decision and it surprised the other agencies. I don’t think the US Attorney and State’s Attorney expected it. They had to scramble.”

We point out that, at this point, the Mayor had just been re-elected, so the political dynamic was different.

“A little different,” he agrees, “but the impression I’ve gotten from people I can’t quote at the moment but very close to it within the mayor’s office is they just recognized that the pressure had built to the point that it was uncontainable. So it was more a political dynamic. It was young activists in the street. It was the building what ultimately became this political firestorm.”

We tell Kalven that re-reading Sixteen Shots, his Feb. 10, 2015 Slate article, published just two weeks before Emanuel was re-elected, was prophetic for its political prediction:

The McDonald footage will come out, but a great deal turns on how it comes out. Will the city be forced to release it in a way that deepens the crisis of public confidence in law enforcement, or will it be released in a way that helps restore the “foundation of trust” between residents and police on which effective law enforcement depends? If the city resists releasing the video until legally compelled to do so, outrage at what it depicts will be compounded by outrage that the city knew its contents (and the autopsy results) in the immediate aftermath of the incident yet withheld that information from the public.

The fate of Laquan McDonald—a citizen of Chicago so marginalized he was all but invisible until the moment of his death—has thus become entwined with that of Mayor Emanuel. It presents his administration with a defining moment.

“The close of the Slate article was just my sense at that point quite early in the process from where we are now,” he tells us, “that the longer they withheld the thing the more appalled people were going to be. Not simply by the atrocity that is depicted in the video, but by the idea that the city had this, knew it, and withheld it from the public.”

Jamie Kalven speaks frequently of the “machinery” that manufactures narratives for the police. And he says that machinery will be on full display as another trial begins next week. Three of the eleven officers who were present at the McDonald shooting have been charged with conspiring to cover up Van Dyke’s actions. It isn’t clear how the three were chosen to be tried, he says.

“There’s a Detective March who really was central to the orchestration of the false reporting, Walsh, Joseph Walsh who was Van Dyke’s partner that day who was closest to the action to actually see what happened and who clearly lied about it. But then the third is an officer named Gaffney who was one of the two first responders. ”

And that officer has been widely recognized as having been patient and professional, Kalven says, calling for a Taser and following McDonald for several minutes before Van Dyke arrived . “They didn’t ask for backup even. They just asked for a taser. It wasn’t clear that they would use it, but that would be the outer limits of the force that they would use.”

“So they have witnessed an appalling event and then they go back to the station house and we will find out more of these details in this trial, but presumably in some fashion the officers present are called into a room and the conversation is not about what happened, it’s about how we are collectively going to justify what happened. I can’t imagine worse working conditions.”

“I think this is why it’s important to understand the machinery as a narrative machinery,” he concludes. “A way of imposing, power imposes itself through narrative, all of that was in the service of a one-paragraph statement that was released that night under the superintendent’s signature released on the morning of October 21stsaying a young man with a knife lunges at police officer. Police officer in self-defense shoots and kills him. What ended up being required to maintain that false narrative proved to be ultimately catastrophic for the Police Department.”

You can visit the Citizens’ Police Data-Base Project at cpdp.co.

You can watch the show by tapping the image at the top of this post.

You can listen to the show’s audio here.